“But Mary kept all these things and pondered them in her heart.”

Alice Havers, 1888

Let’s begin with religion. In most forms they take, religious beliefs share the goal of trying to interpret the great mystery of our existence. Confined as we all are to our own heads with only a few portholes for sensory observation, human life in itself is and always will be a great interpretive conundrum. What is good? What is true? Religion, science, politics, and philosophy all take on these questions. It seems to me that we will never really know for sure, but religion is perhaps the oldest interpretive mode to run at this problem with pluck and determination.

My own relationship with the Catholic Church in which I was raised is complicated. However, it has become increasingly clear to me over the past few years that what I once in the anger of my teenage years dismissed as a monolithic force of evil and oppression is in actuality a rich and morally complex repository of cultural and humanistic learning. With their interrelated moral and metaphysical cosmologies, religions are an extremely sensitive barometer of their adherents’ most cherished values. When people articulate what they think to be good and true in relation to divine authority, they reveal the very pillars that uphold their senses of self, value, and community. To me, the effort to understand such things is interesting in itself. But it also has much broader intellectual value. Thoroughly understanding how and why such ideas and values have developed and changed over time is necessary for a robust critical perspective on the assumptions that underlie our own moral coordinates.

Nor is this lens of reflection in any way monolithic. Indeed, slavers as well as enslaved people and abolitionists articulated their values and explained their actions with Biblical language. In this example paying close attention to both the interpretive strategies and rhetorical uses of Christianity from a critical perspective reveals more about their values and the world that they lived in than historical individuals likely understood themselves in making their claims.

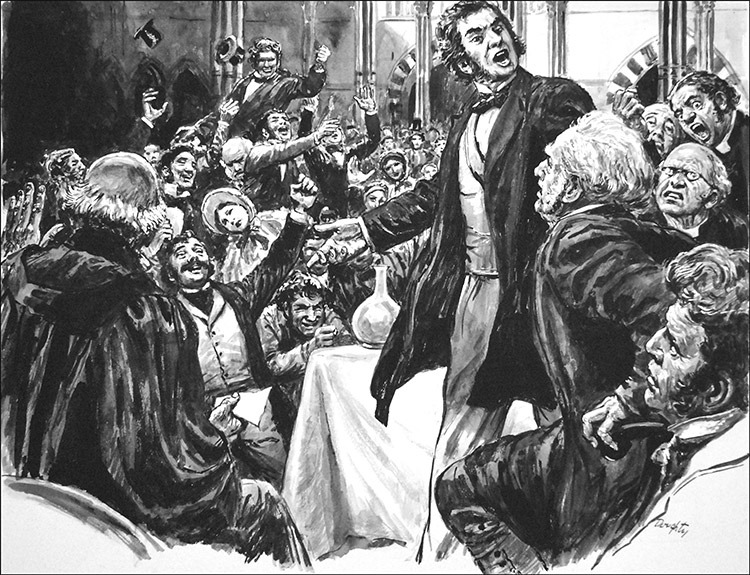

In 1860, Thomas Henry Huxley, a biologist, engaged in a public debate with the bishop and scientist Samuel Wilberforce over Darwin’s theory of natural selection.

Why, then, the nineteenth century in Britain? Here is a time and place where values, ways of life, forms of knowledge, and structures of power changed more rapidly than perhaps anywhere else in the world or in human history. As advances in natural science and philosophy challenged with increasing rigor the literal truthfulness of Christian revelation and its intersections with political power, thinkers of all stripes strove to grapple with these new forms of knowledge and to articulate a system of values that would replace the old. Novelists, especially in realistic works, strove to imagine worlds which would preserve values of religious faith even as they integrated the modern revelations of natural science. Some, like George Eliot, sought to articulate through example how religious values could be translated into secular society. Others, like Oscar Wilde, admired the intellectual and artistic value of contemplating religious revelation, even without believing it to be literally true. But regardless of their individual formal or intellectual choices regarding the representation of religious faith, few Victorian authors abandoned it entirely. It remained a crucial frame of reference for conceptualizing and explaining the highest of human values and aspirations.

Great Britain exerted significant cultural and intellectual influence by virtue of its position of power throughout the nineteenth century. As such, it seems quite important to me to attend to these forms of transition in value if we are to better understand the implicit value structures that underpin our contemporary and secularized coordinates of value. How and why did intellectuals and political leaders translate the values of Christianity to the secular paradigms that they created? What were the ramifications of those translations? Who suffered, who profited? Such knowledge will tell us as much about us as it tells us about the Victorians.